Chuck Dandridge, a Mansfield, Texas resident, became the first adult in the U.S. to receive a newly modified stem cell transplant that uses genetically engineered blood cells from a family member. The milestone was announced by researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center’s Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center in Dallas, where the procedure was performed.

Dandridge’s medical journey began in 2013, with a routine doctor’s visit to check his cholesterol levels; lab tests revealed low blood counts and further testing confirmed Dandridge’s diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome, also called pre-leukemia or MDS. By 2014, the leukemia had progressed to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which, according to the National Cancer Institute, affects more than 20,000 Americans annually.

Dandridge was referred to UT Southwestern’s Simmons Cancer Center, where his leukemia was tested for genetic mutations.

“We wanted to know whether he had specific mutations in his cancer cells,” says

“We found a mutation called IDH 2, which causes the body to produce an abnormal protein that promotes excessive cell growth. If you can target that mutation and stop the abnormal protein from being produced, then cells start behaving normally.”

Dandridge enrolled in a UT Southwestern clinical trial for a therapy called AG-221. He took four pills each morning for the next eight months. During that time, Dandridge saw marked improvement although he did not go into complete remission, according to Vusirikala.

That success made him eligible for a potentially curative stem cell transplant. But finding a donor proved challenging.

“The best chance of finding a full match is usually a full sibling; however, Chuck has no full siblings,” Vusirikala says. Additionally, Dandridge is African American, and minorities are under-represented in the National Marrow Donor Registry—about 70 percent of registry donors are Caucasian. The search for an unrelated donor was unsuccessful.

Vusirikala says that he knew Dandridge’s daughter and his son would be at least a half match. Since using a same-sex donor is preferred, as it reduces the risk of complications, his son Jon, 31, emerged as the best choice. But the risk of graft-versus-host-disease (GvHD) following a transplant using a half-match is very high, so they needed a better way to deal with the GvHD risk.

Once again, Mr. Dandridge volunteered for a cutting-edge clinical trial, known as BP-001, which processed the stem cells used in the transplant to reduce the risk of rejection and engineered blood cells that can be targeted if GvHD develops after the transplant.

The processes being tested in BP-001 are in clinical development by Houston-based Bellicum Pharmaceuticals. The study is evaluating patients with blood cell cancers who have a peripheral blood stem cell transplant from a partially matched relative. Immune cells (T cells) from the related donor are separated from the rest of the stem cells and genetically engineered in the Bellicum laboratory, and then given to the patient along with the stem cell transplant.

The processes being tested in BP-001 are in clinical development by Houston-based Bellicum Pharmaceuticals. The study is evaluating patients with blood cell cancers who have a peripheral blood stem cell transplant from a partially matched relative. Immune cells (T cells) from the related donor are separated from the rest of the stem cells and genetically engineered in the Bellicum laboratory, and then given to the patient along with the stem cell transplant.

These engineered T cells are modified to include a suicide gene with the help of a retrovirus. If the patient develops GvHD after transplant, the side-effect can be treated by giving a drug called rimiducid to activate the suicide gene and cause the activated GvHD-causing cells to be eliminated. The stem cells given for the transplant were also processed prior to giving them back to Dandridge to reduce the risk of graft rejection as well as GvHD.

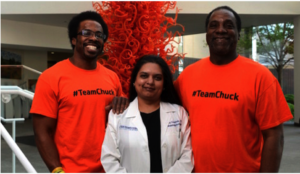

The genetically engineered blood cells were transplanted from Dandrige’s son, Jon, 31, to the father in three, two-hour infusions at William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital in July, 2015, and today the elder Mr. Dandridge’s leukemia is in remission. His immune system is recovering, and the former Norman, Oklahoma YMCA CEO is now mentoring first-time CEOs for the YMCA.

###